By Dan Harmon

Okay, here's that part where the self appointed guru tells you exactly what needs to happen and when.

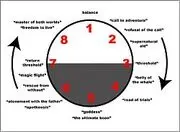

I hope I've made it clear to you before I do that that the REAL structure of any good story is simply circular - a descent into the unknown and eventual return - and that any specific descriptions of that process are specific to you and your story.

Here is my detailed description of the steps on the circle. I'm going to get really specific, and I'm not going to bother saying, "there are some exceptions to this" over and over. There are some exceptions to everything, but that's called style, not structure.

The audience is floating freely, like a ghost, until you give them a place to land.

This free floating effect can be exploited for a while - closing in on the planet Earth; panning across a dirty shed. Who are we going to be? But sooner or later, we need to be someone, because if we are not inside a character, then we are not inside the story.

How do you put the audience into a character? Easy. Show one. You'd have to go out of your way to keep the audience from imprinting on them. It could be a raccoon, a homeless man or the President. Just fade in on them and we are them until we have a better choice.

If there are choices, the audience picks someone to whom they relate. When in doubt, they follow their pity. Fade in on a raccoon being chased by a bear, we are the raccoon. Fade in on a room full of ambassadors. The President walks in and trips on the carpet. We are the President. When you feel sorry for someone, you're using the same part of your brain you use to identify with them.

Lots of modern stories bounce us from character to character in the beginning until we finally settle in some comfortable shoes. The bouncing can be effective, but if it's going on for more than 25% of your total story, you're going to lose the audience. Like anything adhesive, our sense of identity weakens a little every time it's switched or tested. The longer it's been stuck on something, the more jarring it's going to be to yank it away and stick it on someone else.

I wouldn't fuck around if I were you. The easiest thing to do is fade in on a character that always does what the audience would do. He can be an assassin, he can be a raccoon, he can be a parasite living in the racoon's liver, but have him do what the audience might do if they were in the same situation. In Die Hard, we fade in on John McClaine, a passenger on an airplane who doesn't like to fly.

And now the roller coaster car heads up the first hill. Click, click, click....

This is where we demonstrate that something is off balance in the universe, no matter how large or small that universe is. If this is a story about a war between Earth and Mars, this is a good time to show those Martian ships heading toward our peaceful planet. On the other hand, if this is a romantic comedy, maybe our heroine is at dinner, on a bad blind date.

We're being presented with the idea that things aren't perfect. They could be better. This is where a character might wonder out loud, or with facial expressions, why he can't be cooler, or richer, or faster, or a better lover. This wish will be granted in ways that character couldn't have expected.

It's also where a more literal, exterior "Call to adventure" could come in, at the hands of a mysterious messenger, explaining to a dry cleaner that he has been drafted by the CIA.

Frequently, the protagonist "refuses the call." He doesn't want to go to step 3. He's happy as a dry cleaner (at least he thinks he is). The "refusal of the call" is not a necessary ingredient, it's just another oft-used trick to keep us buckled into an identity. We're all scared of change.

Remember: Calls to adventure don't have to come from an actual messenger and wishes don't have to be made out loud.

Fade in on a meek-looking man driving a car. It's raining. Boom. Flat tire. He struggles to keep the car from ditching. He pulls it to the side of the road and stops. He's got fear on his face. He looks out his car window at the pounding rain...

Or to continue with Die Hard: We realize now that John's marriage is rocky. His wife got a nice job in L.A. and he refused to come here with her. Now he's visiting for Christmas. She's using her maiden name in the corporate directory. They're bickering. Things are not right, and if you could read the protagonist's mind, you might find him wishing there was something he could do to save his marriage...

What's your story about? If it's about a woman running from a killer cyborg, then up until now, she has not been running from a killer cyborg. Now she's gonna start. If your story is about an infatuation, this might be the point where our male hero first lays eyes on the object of his desire. Then again, if our protagonist is the object of a dangerous obsession, the infatuation could have been step 2 and this could be the point where the guy says something really, really creepy to her in the office hall. If it's a coming of age story, this could be a first kiss or the discovery of an armpit hair. If it's a slasher film, this is the first kill, or the discovery of a corpse.

The key is, figure out what your "movie poster" is. What would you advertise to people if you wanted them to come listen to your story? A killer shark? Outer space? The Mafia? True love? Everything in grey on that circle, the bottom half, is a "special world" where that movie poster starts being delivered, and everything above this line is the "ordinary world." Step 1, you are the sheriff of a small town. Step 2, strange bites on a murder victim's body. Step 3, holy shit, it's a werewolf.

Remember from tutorial 102 that what's really happening here is a journey into our own unconscious mind, where we can get our shit worked out. A child wakes up and now he's Tom Hanks. His wish to be "big" has been granted. Terrorists attack the Christmas party, and now John McClaine has his chance to literally save his rocky marriage. Neo wakes up in a vat of goo in a world ruled by machines. His ordinary world desire to be a hacker, to fight the system, is going to be put to the test. A suicidal boy starts seeing a therapist. We're going to find out why he tried to kill himself.

It doesn't matter how small or large the scope of your story is, what matters is the amount of contrast between these worlds. In our story about the man changing his tire in the rain, up until now, he wasn't changing a tire. He was inside a dry car. Now, he opens his car door and steps into the pouring rain. The adventure, regardless of its size or subtlety, has begun.

Christopher Vogler calls this phase of a feature script "friends, enemies and allies." Hack producers call it the "training phase." I prefer to stick with Joseph Campbell's title, "The Road of Trials," because it's less specific. I've seen too many movies where our time is wasted watching a hero literally "train" in a forest clearing because someone got the idea it was a necessary ingredient. The point of this part of the circle is, our protagonist has been thrown into the water and now it's sink or swim.

In Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell actually evokes the image of a digestive tract, breaking the hero down, divesting him of neuroses, stripping him of fear and desire. There's no room for bullshit in the unconscious basement. Asthma inhalers, eyeglasses, credit cards, fratty boyfriends, promotions, toupees and cell phones can't save you here. The purpose here has become refreshingly - and frighteningly - simple.

In Romancing the Stone, Michael Douglas cuts the heels off of Kathleen Turner's expensive shoes with a machete. Then he throws her suitcase off a cliff. If she's going to continue to survive in this jungle, she literally needs to drop her excess baggage and lose the fancy pants.

In Die Hard, John McClaine is advised by a terrorist to whom he earlier showed mercy: "The next time you have a chance to kill someone, don't hesitate." John shoots him several times and thanks his corpse for the advice. The cop has begun to fall away, piece by piece, revealing his inner cowboy.

The man in the pouring rain opens his trunk, revealing a pile of laundry and fast food garbage. He tries moving it around, but finally his frustration takes over and he begins tossing things over his shoulder, emptying the contents of his trunk on the side of the road.

We are headed for the deepest level of the unconscious mind, and we cannot reach it encumbered by all that crap we used to think was important.

The road of trial's job is to prepare your protagonist for this meeting. Like a single sperm cell arriving at the egg, your hero-in-the-making just found what they were looking for, even if it's not quite what they knew they were looking for.

I'm using the phrase "meeting with the goddess" because Joseph Campbell thought about these things longer and harder than me. Syd Field calls this "the mid point." Catchy. Robert McKee probably calls it "the nexus of inclination" or something. Unless I'm mistaken, African Americans call it Kwanza.

Whatever you call it, this is a very, very special pivot point. If you look at the circle, you see I've placed the goddess at the very bottom, right in the center. Imagine your protagonist began at the top and has tumbled all the way down here. This is where the universe's natural tendency to pull your protagonist downward has done its job, and for X amount of time, we experience weightlessness. Anything goes down here. This is a time for major revelations, and total vulnerability. If you're writing a plot-twisty thriller, twist here and twist hard.

Twist or no, this is also another threshold, in that everything past this point will take a different direction (namely UPWARD), but note that one is not dragged kicking and screaming through these curtains. One hovers here. One will make a choice, then ascend.

Imagine that you're standing on a pier (1). You see a glimmer through the water and you wonder what it is (2). While leaning to see, you fall off the pier (3). You sink down, deeper and deeper (4) until you come to the floor of the lake and see what was catching the sun's rays.

(5) It's a human skull.

(5) It's a necklace.

(5) It's a tiny, ancient space craft.

(5) It's a quarter. Net worth: 25 cents.

It could be anything, good or bad. A lot of times, it's a healthy dose of both. In a hard-boiled detective story, or a James Bond adventure, this could be a more literal, intimate "meeting," if you know what I mean, with a powerful, mysterious female character. This is a great time for sex or making out with the hot chick, especially if your protagonist has been kung-fuing everybody he meets for the past half hour (or, in Channel 101's case, for the past 60 seconds).

But the goddess doesn't have to be a femme fatale or an angelic damsel. In an all-male or all-female play that takes place around a poker table, the "goddess" could be a character's confession that they lost their job. The goddess can be a gesture, an idea, a gun, a diamond, a destination, or just a moment's freedom from that monster that won't stop chasing you.

In Die Hard, John McClaine, having run over broken glass, is sitting in a bathroom, soaking his bloody feet in the sink. It is at this moment that he finally realizes the true extent of his love for his wife, and what he's been doing wrong in their marriage. He (1) has been too stubborn (2). He uses his walkie talkie, acquired in step (4), to give a message to his wife through his benevolent, happily married, gun-shy counterpart: "She's heard me say 'I love you' a thousand times...but she's never heard me say I'm sorry."

It's not enough to hack and slash your way through symbol after neurotic symbol. The hacking and slashing was a process, that process is over, if only temporarily, and we have reached a second major turn.

The definition of "major" being, of course, in relation to your circle's diameter. Our stranded, rain soaked driver has finished emptying the contents of his trunk on the side of the road. He sees the spare tire and he lets out a very slight, very fast sound of relief. That's all. This is a story about a man changing a tire. That's all the goddess we need.

You might have noticed that, just as (3), the crossing of the threshold, is the opposite of (7) the return, (5), the meeting with the goddess, is the opposite of (1), the protagonist's zone of comfort. Think of (1) as being the arms of mother, however dysfunctional she might be. (5) is a new form of mother, an unconscious version, and there is often a temptation to stay right here. Like at that elf guy's house in Lord of the Rings.

This is very, very important. Movement beyond (5) becomes the protagonist's volition. The water where the sirens sang their seductive song was littered with wrecked ships. The goddess can be the undoing, or the permanent pacification, of non-heroes. It's all fine and well for James Bond to dip his noodle, but he can't lay around here all day. Electropussy might kill him with her flamethrowing lipstick or something.

In (1), we were in the arms of the mother, but were removed by (2), the pull of the father. The need, the longing, the lack of completion, either coming from within or without, drew us to (3) and we were pulled across a threshold into the unknown. We were then transformed (4) into (5), the opposite of a mama's boy: A lady's man.

To reiterate, this doesn't only apply to stories about men having sex. If this is a story of a poor little girl (1) who dreamt of being rich (2) and got adopted by a millionaire (3), having become accustomed to her new lifestyle, (4), she might now be something of a fancy pants (5). Show it with a defineable moment. This might be a good point for her to drive by the orphanage in her limousine.

As you might expect with a circular model like this, there is a lot of symmetry going on, and on the journey back upward, we're going to be doing a lot of referencing to the journey downward.

Just as (1) and (5) are very maternal, feminine, vulnerable moments, (2) and (6) are very paternal, masculine, active moments, regardless of the protagonist's gender.

Think about what really happened at (2). Things were "fine" at (1) but they just weren't quite good enough. That's how we got into this whole mess in the first place.

In Real Genius (I'm really drawing on the classics, now), the dorky kid (1) is recruited for a special college program that's working on a powerful laser (2). He becomes the roommate of a wayward genius whose major is how-to-parrrrrtay (3). Party man teaches Dork how to relax while Dork teaches party man how to focus (4) and as a result, they are able to perfect their laser (5) and get their prestigious accolades. But now a second, more honest call to adventure from an uber-nerd who lives in the steam tunnels: What is that laser for? Why did they have to build it to certain specifications? What did that creepy, popcorn-hating professor have in mind? Sure, they could stay here in this pizza parlor, nursing at the tit of their own prosperity. But then again, they didn't get this far by being irresponsible. It's time to start heading back up to the real world and making things right, Genius style.

There are major, major consequences to that decision. In fact, in a good action movie, this is where our guy simply gets his ass kicked. Robocop, armed with Clarence Boddiker's confession (5), marches into the office of Dick Jones, CEO of the company that built him. He tries to arrest the man that owns him, only to discover that he can't. It's against his programming. Loveable, human Alex Murphy (2) might have been able to pull this off, but bullet-proof, factory-made Robocop can't. Ironic, considering that Murphy's unconscious wish (2) was to be a bulletproof hero ("TJ Laser"). Between his purely mechanical brother, ED-209, and his purely human brothers, the misinformed police, being sicked on him, Robocop barely makes it out of the father's castle in one piece.

Lest you think moments like this are reserved for action films, let's look at a nearly identical scene, which happens to be in Network, which may be the best written film ever made. At this stage of that story, Howard Beale, news anchor turned prophet, is ushered into a board room, where he comes face to face with his creator: CEO of the company that owns the network, Arthur Jensen (played by Ned Beatty). In one of the best written, best performed monologues of the 20th century, Jensen reveals to Beale that capitalism is God, God is capitalism, and having fucked with God, Beale must now atone.

No robots, no explosions, same structure.

That's because this half of the circle has its own road of trials - the road back up. The one down prepares you for the bed of the goddess and the one up prepares you to rejoin the ordinary world.

Having made his peace (5) regarding his marriage, John McClaine now wonders why Hans Gruber, head terrorist, was so desperate for those detonators. He goes back to the roof and discovers that the entire upper portion of the skyscraper is wired to blow. With this realization comes the consequence (6): The giant blonde terrorist - the ED-209 to McClaine's Robocop- descends on him and the two will now battle to the death. Dispatching Blondie is only the first step. The trials on this road come fast and furious. By the time the protagonist gets to (7), the last remaining shreds of his ego will have disappeared and he will have accomplished what Campbell calls the "Atonement with the Father-" The father being this completely non-personal, no-bullshit universe, usually embodied, in action films, by the bad guy (who is often heard to say, in these more arch films, "Nothing personal. Just business.")

In a love story, this is the part where they break up. Now comes the stubble and the dirty dishes and the closed shades. The deep, deep, suicidal depression. The boring relationship with the supposedly better partner. And finally, the realization that nothing was ever more important than him or her.

When you realize that something is important, really important, to the point where it's more important than YOU, you gain full control over your destiny. In the first half of the circle, you were reacting to the forces of the universe, adapting, changing, seeking. Now you have BECOME the universe. You have become that which makes things happen. You have become a living God.

Depending on the scope of your story, a "living God" might be a guy that can finish changing a tire in the rain. Or, in the case of Die Hard, it might be a guy that can appear on the roof, dispatch terrorists with ease and herd 50 hostages to safety while dodging gunfire from an FBI helicopter.

For some characters, this is as easy as hugging the scarecrow goodbye and waking up. For others, this is where the extraction team finally shows up and pulls them out- what Campbell calls "Rescue from Without." In an anecdote about having to change a flat tire in the rain, this could be the character getting back into his car.

For others, not so easy, which is why Campbell also talks about "The Magic Flight."

The denizens of the deep can't have people sauntering out of the basement any more than the people upstairs wanted you going down there in the first place. The natives of the conscious and unconscious worlds justify their actions however they want, but in the grand scheme, their goal is to keep the two worlds separate, which includes keeping people from seeing one and living to tell about it.

This is a great place for a car chase. Or, in a love story, having realized what's important, the hero bursts out of his apartment onto the sidewalk. His lover's airplane leaves for Antartica in TEN MINUTES! John McClaine, who at step (1) was afraid of flying, now wraps a fire hose around his waist and leaps off an exploding building, then shoots a giant window so he can kick through it with his bloody feet.

Strangely enough, he will soon find himself back in the same room where the Christmas party was being held.

In an action film, you're guaranteed a showdown here. In a courtroom drama, here comes the disruptive, sky-punching cross examination that leaves the murderer in a tearful confession. In a love story, the man runs across the tarmac, stops the taxiing airplane, gets on board and says to his lover:

"When I first met you, I thought you were perfect. And then I got used to you being perfect, and everything was perfect, but then I found out you weren't perfect, and we broke up, and then I realized, I'm not perfect, either. Nobody's perfect, and I don't want a perfect person, I just want you. Let's move in together. I'll sleep on the wet spot. You can keep your cat, I'll take allergy medicine. And when you're a hundred years old, I'll clean the shit out of your diaper."

And then, of course, the old woman and/or large black man seated next to the love interest looks at her and says, "Well, what are you waiting for? Go to him!"

Why this strange reaction from old women and large black men? Because the protagonist, on whatever scale, is now a world-altering ninja. They have been to the strange place, they have adapted to it, they have discovered true power and now they are back where they started, forever changed and forever capable of creating change. In a love story, they are able to love. In a Kung Fu story, they're able to Kung all of the Fu. In a slasher film, they can now slash the slasher.

One really neat trick is to remind the audience that the reason the protagonist is capable of such behavior is because of what happened down below. When in doubt, look at the opposite side of the circle. Surprise, surprise, the opposite of (8) is (4), the road of trials, where the hero was getting his shit together. Remember that zippo the bum gave him? It blocked the bullet! It's hack, but it's hack because it's worked a thousand times. Grab it, deconstruct it, create your own version. You didn't seem to have a problem with that formula when the stuttering guy (4) recited a perfect monologue (8) in Shakespeare in Love. It's all the same. Remember that tribe of crazy, comic relief Indians that we befriended at (4) by kicking their biggest wrestler in the nuts? It is now, at (8), as we are nearly beaten by the bad guy, that those crazy sons of bitches ride over the hill and save us. Why is this not Deus Ex Machina? Because we earned it (4).

Everyone thinks the Matrix was successful because of new, American special effects combined with old Hong Kong bootleg style. Those things didn't hurt, but for an example of how well they deliver on their own, watch the fucking sequel. Admit it, it stinks. The writers of the Matrix say in interviews that they assembled The Matrix from elements of their favorite films. They tried to make the movie that they always wanted to see. Ta da. They surrendered to their instincts, to what they knew worked, and as a result, they did what humans do instinctively: They told an instinctively satisfying story about an everyday guy (1) that gets a weird call (2) and, upon following it, realizes that reality was an illusion (3). He learns the ropes (4), talks to the oracle (5), loses his mentor (6), goes back (7) and saves the fucking day (8). It's not perfect, especially in the third act, but try identifying the steps in Matrix Reloaded. Get a slide rule. And a cup of coffee. It's going to be a long, hard slog.

In Die Hard, having killed every terrorist - each time dropping more and more neurotic luggage, McClaine now stands, unarmed, nearly naked, before his wife. There's only one problem. Hans Gruber, the unconscious shadow version of John (is "Hans" German for "John?"), is also here, having "followed" him up to the ordinary world, as shadows are prone to do. He's got a gun to her head. And, he's got one more goon - you know, the guy that played "Nick the Dick" in Bachelor Party (who would've thought he'd last the longest?)

Sometimes Boss Hog doesn't stop at the county line. Sometimes the alien sneaks aboard your escape pod, or the T-Rex starts walking through people's back yards. This is especially liable to happen in more action-oriented life and death stories, where the crossing of the return threshold was down and dirty. Things can get sloppy. You can drag a little more chaos than you wanted through the portal. Worlds can collide. Like Ullyses, coming home to find 50 guys trying to bang his wife, it's time to clean house.

Fortunately, the real John has spent his storytime learning new behaviors, while Shadow John has spent his storytime attempting to cling to his crumbling ego. Real John has learned, in particular, that sometimes your best offense is surrender. He came around the corner with his otherworldly submachine gun, and was ordered to drop it. Now Shadow John, at (8) thinks he has what was so desperately necessary to Real John at (1): Control. He has John's wife as an unwilling hostage. And, of course, like a good villain, Hans would never dream of throwing away the opportunity to gloat as he levels his gun on John.

But John's SMG was empty. He had placed his last two bullets from the unconscious world back into his old, conscious, New York penis pistol, the one he had on the plane, the one that is now taped to his back with ..(blush) Christmas tape. Okay, look, it's a pretty good script up until that point. Anyways, John pulls the concealed gun, shoots Shadow John through his black, uncompromising, German heart, shoots Nick the Dick in the forehead, and, as his wife and Hans nearly both tumble through the broken window, John is able to release his love once and for all by releasing the clasp on the Rolex given to her by an L.A. cokehead yuppy. The watch, and Hans, tumble through the air, the principal from Breakfast Club says "I hope that's not a hostage," and so concludes the 20th century's greatest action film.

Well, not quite. The proper, jive talking, submissive, comic relief black chaueffer has to punch out the improper, hyperintelligent, uppity black computer hacker, thereby making slavery more heroic than terrorism and restoring security to caucasian society. Also, the child-murdering, gun-shy L.A. cop has to blow away the freshly resurrected Blonde terrorist, reacquainting himself with the fact that sometimes, killing the right type of person can be a life affirming act.

Meanwhile, our tire-changing hero starts his car and heads home, with a story to tell his wife.

A good story? Worthy of TV or movies? Of course not. But the tire-changing story uses the barest minimums. Contrast it with one in which, after the man pulls his car to the side of the road, a werewolf opens the door and eats him. The end. Now, you have one sequence with a werewolf in it and one without. Which tells a story? It doesn't matter how cool you think werewolves are, you know the answer instinctively.

You know all of this instinctively. You are a storyteller. You were born that way.

Next in series: Story Structure 105: How TV is Different