By Dan Harmon

I ended my last "tutorial" by saying that next, we'd start examining some 101 videos. But it's been such a long time since then, I thought I might respark first with a total review- with an emphasis on the 5 minute time limit.

When I talk about "story structure" I'm talking about something very scientific, like "geometry." Your story could have "perfect" structure, in that it hits all the resonant points craved by the audience mind, but that won't make it a perfect piece of entertainment. Example:

Once upon a time, there was a thirsty man on a couch. He got up off the couch, went to his kitchen, searched through his refrigerator, found a soda, drank it, and returned to his couch, thirst quenched.

That was "perfect story structure." On the other hand, the story sucked.

Here's a converse example:

Once upon a time, a car exploded. A Navy Seal killed a werewolf. Two beautiful naked women had sex with each other, then a robot shot the moon with a Jesus-powered laser. The world became overpopulated by zombies. The End.

Lot of exciting, creative stuff happening, but very little structure. Again, boo, but the lesbian scene did give me a boner.

What do you want? You want both. You want to be cool, but you're going to be cooler if the structure is there. Cool stuff with no structure is like that perfect scene you recorded when you left the lens cap on. "Guess you had to be there." Show me an army of zombies and I might say "cool zombies," but I'm not going to "be there."

You also want to make sure everything's lit well, and that the audio is clear, and that the edits are well-timed, and it would be great if you had fantastic actors and a makeup artist and a million other ingredients. But we are not talking about makeup right now, or lighting, acting, editing, or how to come up with cool ideas. We're focusing on one very particular aspect of a video: Its structure, the geometry of its story. A little bit helps a little, a lot helps a LOT, having none can cripple you.

The thing about Channel 101 that makes it really easy to analyze structure in action: The five minute time limit. That's 300 seconds, 75 seconds per story quarter, 37.5 per step. And what are those steps? Class?

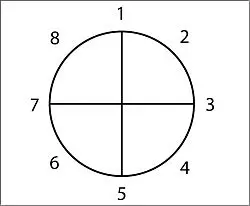

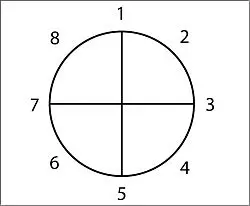

As I've said, the easiest way to visualize these steps is by drawing a circle, dividing it into 4 equal pieces, and writing numbers around it clockwise, with (1) and (5) at the north and south "poles" of the circle, (3) and (7) at the east and west poles.

"You" - who are we? A squirrel? The sun? A red blood cell? America? By the end of the first 37 seconds, we'd really like to know.

"Need" - something is wrong, the world is out of balance. This is the reason why a story is going to take place. The "you" from (1) is an alcoholic. There's a dead body on the floor. A motorcycle gang rolls into town. Campbell phrases: Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, Supernatural Aid.

"Go" - For (1) and (2), the "you" was in a certain situation, and now that situation changes. A hiker heads into the woods. Pearl Harbor's been bombed. A mafia boss enters therapy. Campbell phrase: Crossing of the Threshold. Syd Field phrase: Plot Point 1.

"Search" - adapting, experimenting, getting shit together, being broken down. A detective questions suspects. A cowboy gathers his posse. A cheerleader takes a nerd shopping. Campbell phrases: Belly of the Whale, Road of Trials. Christopher Vogler phrase: Friends, Enemies and Allies.

"Find" - whether it was the direct, conscious goal or not, the "need" from (2) is fulfilled. We found the princess. The suspect gives the location of the meth lab. A nerd achieves popularity. Campbell phrase: Meeting with the Goddess. Syd Field phrase: mid-point. Vogler phrase: Approach to the Innermost Cave.

"Take" - The hardest part (both for the characters and for anyone trying to describe it). On one hand, the price of the journey. The shark eats the boat. Jesus is crucified. The nice old man has a stroke. On the other hand, a goal achieved that we never even knew we had. The shark now has an oxygen tank in his mouth. Jesus is dead- oh, I get it, flesh doesn't matter. The nice old man had a stroke, but before he died, he wanted you to take this belt buckle. Now go win that rodeo. Campbell phrases: Atonement with the Father, Death and Resurrection, Apotheosis. Syd Field phrase: plot point 2

"Return" - It's not a journey if you never come back. The car chase. The big rescue. Coming home to your girlfriend with a rose. Leaping off the roof as the skyscraper explodes. Campbell phrases: Magic Flight, Rescue from Without, Crossing of the Return Threshold.

"Change" - The "you" from (1) is in charge of their situation again, but has now become a situation-changer. Life will never be the same. The Death Star is blown up. The couple is in love. Dr. Bloom's Time Belt is completed. Lorraine Bracco heads into the jungle with Sean Connery to "find some of those ants." Campbell phrases: Master of Both Worlds, Freedom to Live.

AGAIN, SAID DIFFERENTLY: If we assume you're going to use your full 5 minutes, then you've got 1 minute and 15 seconds to for these 3 steps:

- Get the audience to identify with someone or something, - Give that someone or something some kind of need, - And start changing the circumstances.

You've then got another 1:15 to:

- Have that someone or something deal with the new circumstances - And find the thing that was needed.

You've got another 1:15 to:

- Have that someone or something pay the price of the find - And start heading back toward the original circumstances.

And a final 1:15 to:

- show how those original circumstances have changed as a result.

In TV (including Channel 101), that last quarter is a good time to make it very clear to the audience that you've got a series in mind. More can happen. As a "situation changer," your protagonist is going to be going on more journeys (episodes), creating a viable series or "franchise."

You want to go nuts? Think of each of the 8 steps as consisting of 8 microcosmic substeps. Because the act of:

(1) Establishing a protagonist

could be done by showing a guy on a couch for 4 seconds, showing a closeup of his face looking thirsty for 4 seconds, and so on until you've spent 37.5 seconds telling the "story of the guy that drank a soda." Then you could go on to

(2) Establish a need

By telling the 37.5 second story of "the guy whose soda turned out to contain poison:"

It's all in the context of step 2, but cycling through a mini-circle. Then you could tell the 37.5 second story of him going to heaven, followed by the story of him asking around for God, the story of him finding God, the story of God telling him he can only go back to Earth if he agrees to be a dog, etc.

I'm not recommending that you sit there with a compass and a calculator breaking down your story to the point where every 4 second line of dialogue consists of 8 syllables and tells the story of a sentence, but it's possible and sometimes "going there" can help you make decisions or get unblocked.

On the other hand, you can also just shotgun it. So what if you have to spend an extra 11 seconds making the audience love your main character, at the price of some time from other sections of the story? So what if, in today's world, we really don't need to spend a proportionate amount of time saying "happily ever after," at the expense of less karate? Nobody's going to notice. A confidently hand drawn, vaguely egg-shaped circle can be circular enough.

You won't win any prizes for being the Phillip Glass of story structure, especially if it starts compromising your creativity. Follow your bliss. If you know what to do, do it. That's called creativity. If you don't know what to do, THEN listen to some guy like me telling you what you HAVE to do.

Okay, that's the review of my story model. And here are some questions it sometimes raises:

FAQ:

Q: Why do stories have to follow this structure?

A: It's not that stories have to follow this structure, it's that, without some semblance of this structure, it's not recognizable as a story.

I learned about "iconography" from working with Rob Schrab for several years. In cartooning, you have to draw a certain combination of lines before the audience is going to universally recognize what you've drawn.

If I draw a cylinder, I can tell you it's a banana, but I can't make you think "banana" on your own unless I make it yellow, taper the ends and give it some curvature. To further extend this metaphor: Sometimes bananas are green in real life. If I make a green, tapered, curved cylinder, does it look like a banana? It looks like a pepper. You can jump up and down and scream about how you just drew a perfectly good banana, because it looks just as much like a real banana as a yellow one (student filmmaker), but I'm telling you, dude, it's a fucking pepper, UNTIL you put more time and energy into giving it OTHER recognizable banana qualities- for instance, drawing it half peeled. Okay, now it's a green banana. You blew my mind.

Likewise, I'm saying there's 8 steps to "drawing" a universally recognizable story. Can you skip some of them? Yep. I do it all the time. The "road of trials" in Call me Cobra is a guy sitting down at a table. If I had an extra 30 seconds, I would have written that Steve tries on different outfits and personas, saying "I'm the Cobra" in a mirror before deciding on his black suit and going to his meeting with the goddess. But I skipped it. It's implied. The time was needed elsewhere.

Q: Yeah, but why would a human being recognize certain things as stories? I mean, with a banana, we need to know it's a banana so that we know we can eat it. We don't "eat" stories.

A: Yes we do, and our survival as individuals and as communities is dependent on recognizing the edible, nutritious ones. Information can be "empty calories," like a phone book, or it can be downright "poisonous," like a Superbowl halftime show, a Madonna video or footage of a man blowing his brains out. The right kinds of poison can get you high and help you have fun, but it's getting you high because it's fucking with you, it's killing you, and if you don't occassionally eat real story food- a dramatic game of football where your favorite team wins, a meaningful conversation with friends you trust, a good book, a good movie, a good TV show, witnessing a life being saved at the public pool- you are going to wither away and die, psychologically, spiritually and socially speaking.

Q: But I'm sick and tired of cookie-cutter stories about good guys saving the day from bad guys. Some of my favorite movies fly in the face of your story model.

A: If it's really your favorite movie, I absolutely guarantee you it's structured at least somewhat in accordance with this model. You're hearing "good guys and bad guys," but I'm not saying it. I'm saying "protagonist descending and returning."

The very fact that you ARE sick of ordinary movies is evidence that we live and breathe this structure. If you're a subversive punk rock anarchist with a spike through your nose, and you hate "Shrek" because it's a piece of corporate shit, you are craving a descent into the unknown. "You" are expressing a "need" to "go" to an obscure film magazine, "search" for something unique, "find" a gory Japanese horror film, "take" it, "return" to your apartment with it and use it to "change" your friends' minds about cinema. And I think you will find that your "favorite" Japanese gore fest is the one with a recognizable protagonist needing to eat human flesh, going to an orgy, eating everyone there, raping a woman, killing the police and jumping out the window before heading into the night.

Schrab has this video we watch all the time: It's an orientation video designed to teach mentally r*****ed girls about their period. The protagonist is a r*****ed girl. She starts asking questions about periods. She's led into a bathroom by her older sister, and after a very uncomfortable road of trials, things take a turn for the bizarre. I won't go into detail. Not only is the protagonist going on a journey, the audience is, too.

I have taken great pains to avoid any ethical positioning in my observations of structure. Stories are not necessarily about love conquering all, they're not about achieving spiritual balance, they're not about "learning valuable life lessons" and they're not about maintaining order. They're about change. Subversion of order. By the way, "Shrek" had not-so-good structure.

Good structure is the best weapon we can use in the fight against corporate garbage because good structure costs nothing, is instinctive to the individual and important to the audience. For all their money, computers and famous actors, the Hollywood factory is constantly being challenged and often buried by individuals like you, people who started by realizing that they were sick of the shit they were seeing and wrote a good story from the deepest level of their unconscious mind. I am trying to show you how to make your own gunpowder. You can use it to make pretty fireworks or you can use it to blow up a building full of innocent babies, it's not my place to care.

Q: If this stuff is instinctive, why does it have to be "taught?" A: Because we don't live in the real world anymore. We are not in tune with our instincts. Babies know how to swim when they're born but some adults sink like a stone until another adult shows them some moves.

Q: If you're so great, why haven't you written anything good? A: Isn't that always the way? I'm not a great writer. I'm just a guy that's been obsessed with story structure for the last seven years, non stop. Like I said at the beginning, perfect structure is not synonymous with "good show." This is about what audiences recognize as stories, not about how to be a good writer.

Q: I disagree with your model, I don't think all stories are required to do this or that. A: Prove me wrong. It'd be a great exercise. Don't have a protagonist. Or do have one, but don't give [it] a need. Or have a protagonist with a need whose circumstances never change. Or have a protagonist with a need enter a new set of circumstances, fail to adapt and never find what they needed. Or have them do everything but return. The first lesson you'll learn is that it's pretty hard to actively defy this story model. As soon as you get in the zone and you're writing something that's making you happy, you're going to realize with horror that you've accidentally nailed one of the story steps at exactly the right time.

End of the series.